Marvelous Misadventures in Bioinformatics

A blog on some snippets of my work in bioinformatics. Hopefully you find something useful here and avoid stupid mistakes I made.

Natural language processing: Word2Vec

In natural language processing, individual words can be embedded into vectors based on a pretrained model. Thesse embeddings are vectors representing the word in a high-dimensional space, and often are feature-rich, providing us with semantic meaning. One such pretraining algorithm is word2vec proposed by Mikolov et al. from Google in 2013. Although a bit outdated and outperformed by more sophisticated models, word2vec vectors has some interesting properties that reveal about our written/spoken language.

Prerequisite

- gensim

- scipy

Installation

pip install gensim

pip install scipy

Usage

-

Import gensim and load the word2vec model

import gensim.downloader as api model = api.load('word2vec-google-news-300')This will download the word2vec pretrained word vector model (when initializing for the first time) pretrained on the Google News dataset containing about 100 billion words. The vocabulary is about 3 million words.

-

Word embeddings can be retrieved by parsing word into the model.

Example: the word ‘dog’

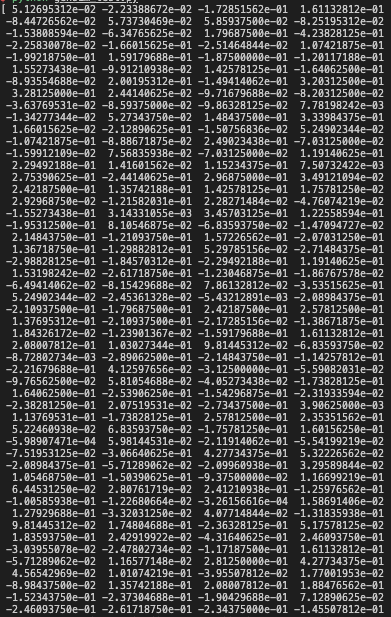

dog = model['dog'] print(dog)will yield a vector like this

Running

print(dog.shape)will yield a vector of size (300,). This means that each word that gets parsed into word2vec will be embedded into a vector with 300 dimensions. These values are on a continous scale (i.e. float values) that captures the semnatic meaning of the word embedded.

-

You can retrieve words that are most similar to the word ‘dog’ by using

print(model.most_similar([dog], topn = 3))This retrieves the 3 words that resembles most like the word ‘dog’. Adjust the topn variable to retrieve the top-n most similar words.

Output:

[('dog', 1.0), ('dogs', 0.8680489659309387), ('puppy', 0.8106428384780884)]

The most similar 3 words to the word ‘dog’ are ‘dog’, ‘dogs’ and ‘puppy’. This does make sense, albeit a bit useless, as the first two words are just reiterating the same word and its plural form.

The 3rd most similar word ‘puppy’ reveal that ‘dog’ and ‘puppy’ are similar, which is logical as the latter is the young of the former.

-

You can get the distance between two vectors by using scipy. (Other methods are available)

import scipy.spatial.distance as dist print(dist.euclidean(model['dog'], model['cat']))This will give the distance of the elucidean distance between the vector embeddings for the words ‘dog’ and ‘cat’.

output:

2.081533670425415 -

Interesting stuff happens when we do some linear operations on a combination of these vectors that reveal more about the semantics of the embeddings.

test_vec = model['queen'] - model['woman'] + model['man'] assert test_vec.shape == (300,) #ensure that the ouput vector is of shape (300,)Here we remove the vector encoding for the term ‘woman’ from the word ‘queen’ and add ‘man’ to it.

print(model.most_similar([test_vec], topn = 3))Will yield

Output:

[('queen', 0.8393025994300842), ('king', 0.7046408653259277), ('queens', 0.6252749562263489)]The resulting vector from our operation most resembles the words

queen,kingandqueens. While the most similar word is just the reiteration of the wordqueen. The second wordkingis fascinating. It makes linguistic and logical sense when you remove the concept ofwomanfrom the wordqueenand reintroduceman, the resulting output would somewhat resembleking. This implies that in the 300-dimension vector, there are vector(s) that encodes for concepts of gender and royalty.

Note: While this example shows embeddings in action quite well, the underlying training dataset comes from the google news dataset, which introduces biases. Words that are commonly used in news are overrepresented while other words are under-represented.

Note 2: This example does not work for words that are not in the vocabulary

try:

print(model['mussolini'])

except:

print('The word is not found')

Output: The word is not found

will reveal that the word italin dictator mussolini is not in the corpus.

Another example showing this bias is by running:

print(model.most_similar([model["science"]], topn = 3))

Will yield

[('science', 1.0000001192092896), ('faith_Jezierski', 0.6965422034263611), ('sciences', 0.6821076273918152)]

Which is quite strange. What is faith_Jezierski doing near the vector for science?

It turns out that this vector might be related to the news that Copernicus, the astronomer who proposed the heliocentric system, was buried with catholic honours in 2010. This made the rounds in the news, prompting the model to pick up faith_Jezierski to be associated with the word science. Jezierski likely refers to Jacek Jezierski, a Polish bishop that pushed for the posthumous recognition of Copernicus, and that this name is also referenced in the news.

This shows that the training corpus of pre-trained models will influence the embeddings of your queries, and most likely introduce biases.

Reference

- https://arxiv.org/abs/1301.3781

- https://code.google.com/archive/p/word2vec/